From the Arid Lands Newsletter (Spring/Summer 1994, Issue No. 35; ISSN: 1092-5481):

http://ag.arizona.edu/OALS/ALN/aln35/TOC35.html

"This is the most beautiful place on earth," Abbey declared on page one of Desert Solitaire. The place he meant was the slickrock desert of southeastern Utah, the "red dust and the burnt cliffs and the lonely sky - all that which lies beyond the ends of the roads."

Desert Solitaire, drawn largely from the pages of a multi-volume journal the author began in 1956 and kept over several seasons as a ranger in Arches National Monument (now a national park), was published "on a dark night in the dead of winter" in 1968. The book later moved the novelist Larry McMurtry to declare Abbey "the Thoreau of the American West," but it was greeted at first with little acclaim and slow sales. Since then, readers have supported the book through a long history of printings that led to what the author declared to be the "new and revised and absolutely terminal edition" brought out by The University of Arizona Press in 1988. It is that twentieth anniversary edition from which our excerpt, from the chapter titled "Terra Incognita: Into the Maze," is taken:

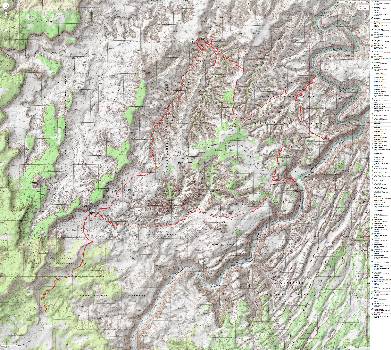

We camp the first night in the Green River Desert, just a few miles off the Hanksville road, rise early and head east, into the dawn, through the desert toward the hidden river. Behind us the pale fangs of the San Rafael Reef gleam in the early sunlight; above them stands Temple Mountain - uranium country, poison springs country, headwaters of the Dirty Devil. Around us the Green River Desert rolls away to the north, south and east, an absolutely treeless plain, not even a juniper in sight, nothing but sand, blackbrush, prickly pear, a few sunflowers. Directly eastward we can see the blue and hazy La Sal Mountains, only sixty miles away by line of sight but twice that far by road, with nothing whatever to suggest the fantastic, complex and impassable gulf that falls between here and there. The Colorado River and its tributary the Green, with their vast canyons and labyrinth of drainages, lie below the level of the plateau on which we are approaching them, "under the ledge," as they say in Moab.

The scenery improves as we bounce onward over the winding, dusty road: reddish sand dunes appear, dense growths of sunflowers cradled in their leeward crescents. More and more sunflowers, whole fields of them, acres and acres of gold - perhaps we should call this the Sunflower Desert. We see a few baldface cows, pass a corral and windmill, meet a rancher coming out in his pickup truck. Nobody lives in this area but it is utilized nevertheless; the rancher we saw probably has his home in Hanksville or the little town of Green River.

Halfway to the river and the land begins to rise, gradually, much like the approach to Grand Canyon from the south. What we are going to see is comparable, in fact, to the Grand Canyon - I write this with reluctance - in scale and grandeur, though not so clearly stratified or brilliantly colored. As the land rises the vegetation becomes richer, for the desert almost luxuriant: junipers appear, first as isolated individuals and then in stands, pinyon pines loaded with cones and vivid colonies of sunflowers, chamisa, golden beeweed, scarlet penstemon, skyrocket gilia (as we near 7000 feet), purple asters and a kind of yellow flax. Many of the junipers - the females - are covered with showers of light-blue berries, that hard bitter fruit with the flavor of gin. Between the flowered patches and the clumps of trees are meadows thick with gramagrass and shining Indian ricegrass_and not a cow, horse, deer or buffalo anywhere. For God 's sake, Bob, I'm thinking, let 's stop this machine, get out there and eat some grass! But he grinds on in singleminded second gear, bound for Land's End, and glory.

Flocks of pinyon jays fly off, sparrows dart before us, a redtailed hawk soars overhead. We climb higher, the land begins to break away: we head a fork of Happy Canyon, pass close to the box head of Millard Canyon. A fork in the road, with one branch old, rocky and seldom used, the other freshly bulldozed through the woods. No signs. We stop, consult our maps, and take the older road; the new one has probably been made by some oil exploration outfit.

Again the road brings us close to the brink of Millard Canyon and here we see something like a little shrine mounted on a post. We stop. The wooden box contains a register book for visitors, brand-new, with less than a dozen entries, put here by the BLM--Bureau of Land Management. "Keep the tourists out," some tourist from Salt Lake City has written. As fellow tourists we heartily agree.

On to French Spring, where we find two steel granaries and the old cabin, open and empty. On the wall inside is a large water-stained photograph in color of a naked woman. The cowboy's agony. We can't find the spring but don't look very hard, since all of our water cans are still full.

We drive south down a neck of the plateau between canyons dropping away, vertically, on either side. Through openings in the dwarf forest of pinyon and juniper we catch glimpses of hazy depths, spires, buttes, orange cliffs. A second fork presents itself in the road and again we take the one to the left, the older one less traveled by, and come all at once to the big jump and the head of the Flint Trail. We stop, get out to reconnoiter.

The Flint Trail is actually a jeep track, switchbacking down a talus slope, the only break in the sheer wall of the plateau for a hundred sinuous miles. Originally a horse trail, it was enlarged to jeep size by the uranium hunters, who found nothing down below worth bringing up in trucks, and abandoned it. Now, after the recent rains, which were also responsible for the amazing growth of grass and flowers we have seen, we find the trail marvelously eroded, stripped of all vestiges of soil, trenched and gullied down to bare rock, in places more like a stairway than a road. Even if we can get the Land Rover down this thing, how can we ever get it back up again?

But it doesn't occur to either of us to back away from the attempt. We are determined to get into The Maze. Waterman has great confidence in his machine; and furthermore, as with anything seductively attractive, we are obsessed only with getting in; we can worry later about getting out.

Munching pinyon nuts fresh from the trees nearby, we fill the fuel tank and cache the empty jerrycan, also a full one, in the bushes. Pine nuts are delicious, sweeter than hazelnuts but difficult to eat; you have to crack the shells in your teeth and then, because they are smaller than peanut kernels, you have to separate the meat from the shell with your tongue. If one had to spend a winter in Frenchy's cabin, let us say, with nothing to eat but pinyon nuts, it is an interesting question whether or not you could eat them fast enough to keep from starving to death. Have to ask the Indians about this.

Glad to get out of the Land Rover and away from the gasoline fumes, I lead the way on foot down the Flint Trail, moving what rocks I can out of the path. Waterman follows with the vehicle in first gear, low range and four-wheel drive, creeping and lurching downward from rock to rock, in and out of the gutters, at a speed too slow to register on the speedometer. The descent is four miles long, in vertical distance about two thousand feet. In places the trail is so narrow that he has to scrape against the inside wall to get through. The curves are banked the wrong way, sliding toward the outer edge, and the turns at the end of each switchback are so tight that we must jockey the Land Rover back and forth to get it through them. But all goes well and in an hour we arrive at the bottom.

Here we pause for a while to rest and to inspect the fragments of low-grade, blackish petrified wood scattered about the base of a butte. To the northeast we can see a little of The Maze, a vermiculate area of pink and white rock beyond and below the ledge we are now on, and on this side of it a number of standing monoliths - Candlestick Spire, Lizard Rock and others unnamed.

Close to the river now, down in the true desert again, the heat begins to come through; we peel off our shirts before going on. Thirteen miles more to the end of the road. We proceed, following the dim tracks through a barren region of slab and sand thinly populated with scattered junipers and the usual scrubby growth of prickly pear, yucca and the alive but lifeless-looking blackbrush. The trail leads up and down hills, in and out of washes and along the spines of ridges, requiring fourwheel drive most of the way.

After what seems like another hour we see ahead the welcome sight of cottonwoods, leaves of green and gold shimmering down in a draw. We take a side track toward them and discover the remains of an ancient corral, old firepits, and a dozen tiny rivulets of water issuing from a thicket of tamarisk and willow on the canyon wall. This should be Big Water Spring. Although we still have plenty of water in the Land Rover we are mighty glad to see it.

In the shade of the big trees, whose leaves tinkle musically, like gold foil, above our heads, we eat lunch and fill our bellies with the cool sweet water, and lie on our backs and sleep and dream. A few flies, the fluttering leaves, the trickle of water give a fine edge and scoring to the deep background of - silence? No - of stillness, peace.

I think of music, and of a musical analogy to what seems to me the unique spirit of desert places. Suppose for example that we can find a certain resemblance between the music of Bach and the sea; the music of Debussy and a forest glade; the music of Beethoven and (of course) great mountains; then who has written of the desert?

Mozart? Hardly the outdoor type, that fellow - much too elegant, symmetrical, formally perfect. Vivaldi, Corelli, Monteverdi? - cathedral interiors only - fluid architecture. Jazz? The best of jazz for all its virtues cannot escape the limitations of its origin: it is indoor music, city music, distilled from the melancholy nightclubs and the marijuana smoke of dim, sad, nighttime rooms: a joyless sound, for all its nervous energy.

In the desert I am reminded of something quite different - the bleak, thin-textured work of men like Berg, Schoenberg, Ernst Krenek, Webern and the American, Elliot Carter. Quite by accident, no doubt, although both Schoenberg and Krenek lived part of their lives in the Southwest, their music comes closer than any other I know to representing the apartness, the otherness, the strangeness of the desert. Like certain aspects of this music, the desert is also a-tonal, cruel, clear, inhuman, neither romantic nor classical, motionless and emotionless, at one and the same time - another paradox - both agonized and deeply still.

Like death? Perhaps. And perhaps that is why life nowhere appears so brave, so bright, so full of oracle and miracle as in the desert.

Waterman has another problem. As with Newcomb down in Glen Canyon - what is this thing with beards? - he doesn't want to go back. Or says he doesn't. Doesn't want to go back to Aspen. Where the draft board waits for him, Robert Waterman. It seems that the U.S. Government - what country is that? - has got another war going somewhere, I forget exactly where, on another continent as usual, and they want Waterman to go over there and fight for them. For IT, I mean - when did a government ever consist of human beings? And Waterman doesn't want to go, he might get killed. And for what?

As any true patriot would, I urge him to hide down here under the ledge. Even offer to bring him supplies at regular times, and the news, and anything else he might need. He is tempted - but then remembers his girl. There's a girl back in Denver. I'll bring her too, I tell him. He decides to think it over.

In the meantime we refill the water bag, get back in the Land Rover and drive on. Seven more miles rough as a cob around the crumbling base of Elaterite Butte, some hesitation and backtracking among alternate jeep trails, all of them dead ends, and we finally come out near sundown on the brink of things, nothing beyond but nothingness - a veil, blue with remoteness - and below the edge the northerly portion of The Maze.

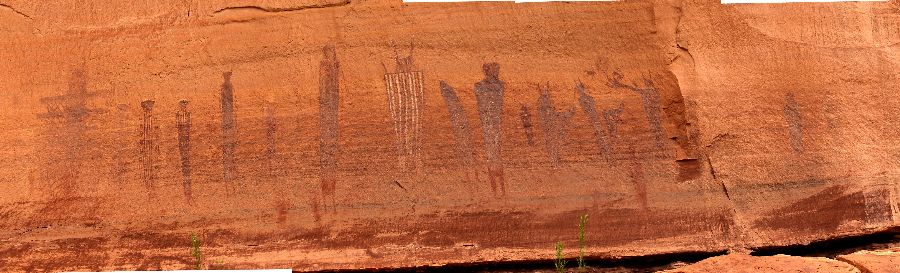

We can see deep narrow canyons down in there branching out in all directions, and sandy floors with clumps of trees--oaks? cottonwoods? Dividing one canyon from the next are high thin partitions of nude sandstone, smoothly sculptured and elaborately serpentine, colored in horizontal bands of gray, buff, rose and maroon. The melted ice-cream effect again - Neapolitan ice cream. On top of one of the walls stand four gigantic monoliths, dark red, angular and square-cornered, capped with remnants of the same hard white rock on which we have brought the Land Rover to a stop. Below these monuments and beyond them the innumerable canyons extend into the base of Elaterite Mesa (which underlies Elaterite Butte) and into the south and southeast for as far as we can see. It is like a labyrinth indeed - a labyrinth with the roof removed.

Very interesting. But first things first. Food. We build a little juniper fire and cook our supper. High wind blowing now - drives the sparks from our fire over the rim, into the velvet abyss. We smoke good cheap cigars and watch the colors slowly change and fade upon the canyon walls, the four great monuments, the spires and buttes and mesas beyond.

What shall we name those four unnamed formations standing erect above this end of The Maze? From our vantage point they are the most striking landmarks in the middle ground of the scene before us. We discuss the matter. In a far-fetched way they resemble tombstones, or altars, or chimney stacks, or stone tablets set on end. The waning moon rises in the east, lagging far behind the vanished sun. Altars of the Moon? That sounds grand and dramatic - but then why not Tablets of the Sun, equally so? How about Tombs of Ishtar? Gilgamesh? Vishnu? Shiva the Destroyer?

Why call them anything at all? asks Waterman; why not let them alone? And to that suggestion I instantly agree; of course - why name them? Vanity, vanity, nothing but vanity: the itch for naming things is almost as bad as the itch for possessing things. Let them and leave them alone - they'll survive for a few more thousand years, more or less, without any glorification from us.

But at once another disturbing thought comes to mind: if we don't name them somebody else surely will. Then, says Waterman in effect, let the shame be on their heads. True, I agree, and yet - and yet Rilke said that things don't truly exist until the poet gives them names. Who was Rilke? he asks. Rainer Maria Rilke, I explain, was a German poet who lived off countesses. I thought so, he says; that explains it. Yes, I agree once more, maybe it does; still - we might properly consider the question strictly on its merits. If any, says Waterman. It has some, I insist.

Through naming comes knowing; we grasp an object, mentally, by giving it a name - hension, prehension, apprehension. And thus through language create a whole world, corresponding to the other world out there. Or we trust that it corresponds. Or perhaps, like a German poet, we cease to care, becoming more concerned with the naming than with the things named; the former becomes more real than the latter. And so in the end the world is lost again. No, the world remains - those unique, particular, incorrigibly individual junipers and sandstone monoliths - and it is we who are lost. Again. Round and round, through the endless labyrinth of thought - the maze.

.jpg)