HST, Hiking the High Sierra Trail

Septuagenarian Transnavigation of the High Sierra Trail

Visiting:

High Sierra Trail, Nine Mile, Hamilton Lakes, Kaweah Gap, Great Western Divide, Big Arroyo,

Moraine Lake, Kern River, Crabtree Meadow, Guitar Lake,

and Mount Whitney

71 miles

ERM = 161.4

August 17 - 25, 2020

By Wild Vagabond (AKA Rob Jones)

Text and photos

© copyright by Rob Jones

|

|

|---|

HST above Guitar Lake, Early Morning, Day 8

(Click the image to see the map)

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

Pika, HST Mascot

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

Reflection in Hamilton Lake, Day 3

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

Barry on the way to Kaweah Gap, Day 3

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

Hamilton Lake, Day 3

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

Near Precipice Lake, Day 3

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

Reflections of Precipice Lake, Day 3

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

Moraine Lake, Day 4

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

Sky Parlor Meadow and Kaweah Range, Day 5

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

Hitchcock Lakes and smoke rolling in, Day 8

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

On Whitney, Day 8

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

Panorama of the Guitar Lake area, Day 7, 890kb, 900 x 4011

(Click the image to see the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

movie - Guitar Lake area from near start of side trail to Whitney, Day 8; 22 mb

(Click the image to view the movie)

|

|---|

|

.

|

|---|

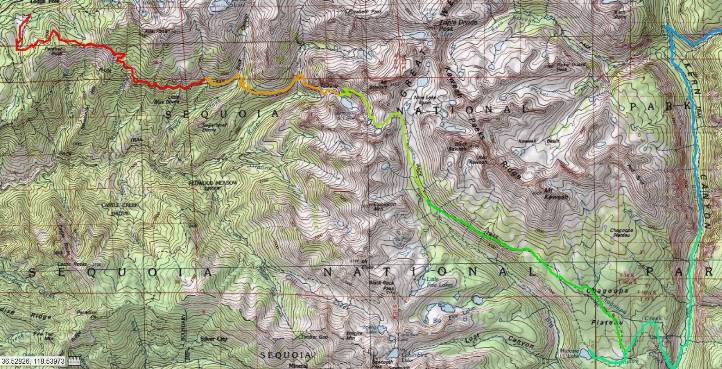

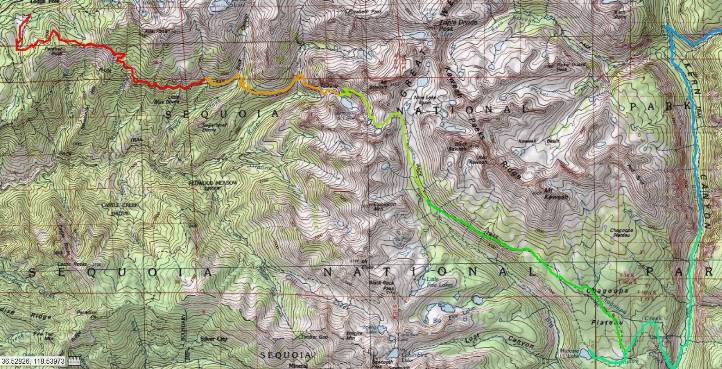

Map - High Sierra Trail - total map (days 1-8), an HTML map by gps-visualizer. You can move around in this map.

It's web-based and may go away, so I've added individual day maps in the report below.

(Click the image to see the map)

|

|---|

|

Co-adventurer: Barry Brenneman

Camera - Panasonic DMC-ZS70

Septuagenarian - A person who is 70 years old or between the ages of 70 and 80.

“Then it seemed

to me that the Sierra should be called, not the Nevada or Snowy Range, but the Range of

Light. And after ten years of wandering and wondering in the heart of it … it still seems

above all others."

John Muir

"Estranged from Beauty –

none can be –

For Beauty is Infinity –

And power to be finite ceased

Before Identity was leased."

- Emily Dickinson

"Between every two pines is a doorway to a

new world".- John Muir

Background/Preliminary: My trail name is Wild Vagabond. Many years ago,

I "earned" this trail name in The Grand Canyon, and brought it with me to subsequent hikes. The website

name "wildernessvagabond.com" evolved from the trail name.

This is a trip report about hiking the High Sierra Trail, HST, from West to East,

across the Sierra Range.

The ERMs, Energy Required Miles, are calculated using the

Gaia GPS app. See the

bottom of the report for a description of ERMs.

Here are my journal notes, some photos, and the daily data and trip map.

ERM = Energy Required Miles. A mile is added for

every 500' elevation gain or

loss. It's a very serviceable method of estimating energy required miles. ERM was initially used in Trails

of the Tetons (long out of print) by Paul Petzold, founder of NOLS. It's a wonderfully useful concept and

application. Add one mile for each 500' up AND down to distance = ERM. I use ERMs to calculate what the actual

day is like. It's a very serviceable method of estimating energy required miles.

Using ERMs does not account for the 'texture' of the route or trail - that

is, rocky, boulders, no trail, slimy mud, etc., yet does help approximate the route.

There is additional information about the valididy of using ERMS at the end of this report.

Day -1 prelim photos - HST

Prelim, Driver: -1. Basin and Range Cordillera Romp: To Lone Pine Campground. Camp @ 6,000'.

Rolling over the cords of mountains, the cordillera, that form the basin and range topography and

ecosystems, it's becoming increasingly hot. A baker. Basin and Range, a terrific book by John McPhee.

Yowee, it's 129°F in Furnace Creek, Death Valley. One's skin begins to crinkle and contract, as if in

a convection oven. Barry and I are off the Colorado Plateau and into the gathering heat.

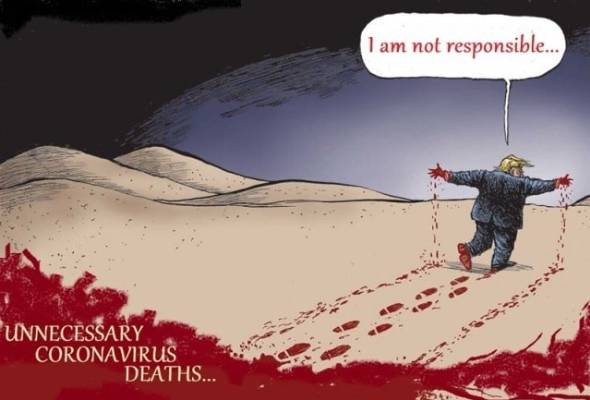

We're self shuttling because the MAGAvirus has closed down the shuttle services, many

campgrounds, motels, restaurants, all manner of civilization. The MAGAites have little interest in civilization anyway, so they are fine.

After electing an orange clown pufferfish, one would indeed expect the evisceration of health care, environment, clean water and air,

worker protection, the rule of law, basic human decency, that sort of stuff. It did not have to be this way. The primary job of the

president of the United States is to keep its citizenry safe. Yet, the cheeto abdicated and denied all responsibility to marshal resources,

react pro-actively and timely and with science. trump stated "I am not responsible." Wow, this is true, one of the few truths issued by

this turd fondler. trump acted based only on self interest, his reaction was a selfish political one, not actions to protect the American people.

Look at South Korea. Their early and non-political actions allowed their society and economy to open early. We will remain bogged down

in the mess created and still fostered by the gop for many more months (no masks at rallies, no help with materials, no cohesive federal plan

or response).

Eventually, we reach Lone Pine and drive up the Whitney Portal Road to Lone Pine Campground

where it's 50° cooler than at Furnace Creek by bedtime.

Day 0 prelim photos - HST

Prelim, Driver Day 0. Sierra Circler: To Stony Creek CG.

Barry and I are up and on the road to Whitney Portal to drop Barry's car at the Portal

for the return shuttle. Extra food for the return trip goes into a bucket obtained from the NPS and used in previous VIP

(Volunteer In Park) adventures, organizing food for the mule ride (food transported) into The Canyon. The bucket then

goes into a trailhead Bear box at Whitney Portal. (Be sure to label and date (date you will pick up the items) anything you

leave in the Bear box.)

Read about the VIP trips and other Canyon adventures here ----> click

Next, we circle around the Southern end of the Range, miles mounting on the trip odometer. The

Sierra Circle is around 320 miles, on top of the 500 from Day -1. Tiring.

Yet now we're lounging in comfy chairs under what may be a Jeffery Pine, enjoying simple beer

cooled in a square bucket from the Phantom Water Treatment Plant at the bottom of The Canyon, Grand Canyon. Deluxe. The bucket contains

ice Barry purchased at Stony Creek Village. We are pleased that natural quiet prevails in this campground, at least tonight. RVs and generator

noise are absent. Wondrous.

Because of the MAGAvirus and trump's inept reaction to it, I've made and lost a few campground

reservations in preparation for this adventure. We thought we would end up in an at-large camping area just outside the park, yet a last-minute

check revealed an open site at Stony CG, a CG where I had previously made, and had canceled, a reservation. Persistence sometimes rules the day.

A vole makes his appearance while refashioning his burrow (California Meadow Vole?). Lounging in

our chairs, we observe him darting partially out of the burrow, pushing out debris, collecting something to eat, then darting back under the

ground. His feet appear to be curved, a good digging design.

Tonight is much more pleasant than last night because we're among the pines, natural quiet rules,

and there's a hint of refreshing coolness to the air.

Sequoia National Park is in the southern Sierra Nevada. The park was established

on September 25, 1890 to protect 404,064 acres (631 sq mi; 163,519 ha; 1,635 km2) of forested

mountainous terrain. Encompassing a vertical relief of nearly 13,000 feet (4,000 m), the park

contains the highest point in the contiguous United States, Mount Whitney, at 14,505 feet (4,421 m)

above sea level. The park is south of, and contiguous with, Kings Canyon National Park; the two parks

are administered by the National Park Service together as the Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks,

SEKI. UNESCO designated the areas as Sequoia-Kings Canyon Biosphere Reserve in 1976.

The park is notable for its giant sequoia trees, including

the General Sherman tree, the largest tree on Eaarth. The General Sherman tree grows in the

Giant Forest, which contains five of the ten largest trees in the world. The Giant Forest is connected

by the Generals Highway to Kings Canyon National Park's General Grant Grove, home of the General

Grant tree among other giant sequoias. The park's giant sequoia forests are part of 202,430 acres

(316 sq mi; 81,921 ha; 819 km2) of old-growth forests shared by Sequoia and Kings Canyon

National Parks. The parks preserve a landscape that still resembles the southern Sierra Nevada

before Euro-American settlement. (paraphrased from the wikipedia)

Although Congress created Sequoia and Kings Canyon Parks in

the southern Sierra Nevada at different times, they share miles of boundary. Sequoia was America’s second

national park designated in 1890, after Yellowstone NP in 1872. General Grant National Park, the forerunner

of Kings Canyon, was the third, established in 1940. (paraphrased from the Sequoia NP site)

|

|---|

Muir knows best

(Click the image to see the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

"Writing is like the life of a glacier;

one eternal grind". - John Muir

"The mountains are calling and I must go".

- John Muir

"Wilderness is not only a haven for native plants

and animals, but it is also a refuge from society. It's a place to go to hear the wind and little else, see the

stars and the galaxies, smell the pine trees, feel the cold water, touch the sky and the ground at the same time,

listen to coyotes, eat fresh snow, walk across the desert sands, and realize why it's good to go outside of the city

and the suburbs.".

- John Muir

|

|---|

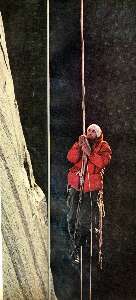

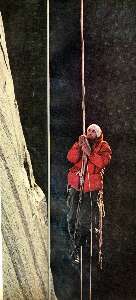

First ascent of El Capitan (Argosy article, 22mb) featuring my friend, George

Whitmore

(Click the 10 page pdf - 22 MB)

|

|---|

|

"In every walk with Nature one receives

far more than he seeks". - John Muir

(Photos and the report of the trip continue below.)

"Keep close to Nature's heart...and break clear

away, once in awhile, and climb a mountain or spend a week in the woods. Wash your spirit clean".

- John Muir

Three map versions for your scrutiny: (the first version is fastest to load, the pdf version is good for printing, and the third map is

a web-based map that can be enlarged. You can change the base map (topo, etc.) and move across the HST. It will probably stop working

at some point and this is the reason I added the first two map formats.)

Alta to 9-mile----> click for a JPG map.

Alta to 9-mile----> click for a pdf map (large file,

decent for printing).

Another version of the map can be found here.

This web version can be enlarged and may be more useful than the above maps, assuming that

it works for you. ----> click here for the GPS visualizer map - and roam at will.

Day -1 photos - HST

Day 1: Path of the Panther. Alta/Wolverton Trailhead to Nine Mile: 9.2 miles;

ERM = 22.2, elevation gain of 3400', loss of 3100'. Camp @ 7600'.

The trail climbs steadily through yuge firs and the occasional pine, angling for the

Panther Gap at somewhere over 8600 feet. "This is definitely the more difficult entrance to the HST, High Sierra Trail," we grunt,

toting Bear cans overflowing with food for 9 days, 8 nights hiking West to East across and through the Sierra. Glorious, yet hefty.

An HST permit to start from Crescent Meadow wasn't available, so this is our daily quest, hiking the path of the Panther, then

dipping down to join the HST.

Bîggly Bear tracks grace the dusty trail as we descend from the Mehrten Meadow junction.

Bear scat is also seen, yet no Bears.

Rolling, lilting, the HST undulates to the Nine Mile drainage, accompanied by sporadic flurries

of rain. And, the thimbleberries are just right alongside the HST, occasionally bringing all travel to a delectable stop.

Now, after a quick dip in the frigid stream, Barry and I are cooking dinner on a bluff

overlooking the stream as it cascades over polished alabaster granite bedrock.

Barry and I enjoy chatting with Nathan and Colten, who canceled their

quest to climb the tablelands above the HST because of horrendous weather, including lightning on this exposed plateau.

Doe and twin fawns slip silently along the edge of the well inhabited Nine Mile drainage

as dusk turns to dark.

"“What would it be like to live in this

place? Could a man ever grow weary of such a home? Someday…I shall make the experiment, become an ancient

baldheaded troglodyte with a dirty white beard tucked in my belt, be a shaman, a wizard, a witch doctor

crazy with solitude, starving on locusts and lizards, feasting from time to time upon lost straggler boy

scout. Madness: of course a man would go mad from the beauty and the loneliness, both equally mysterious.

But perhaps it would be – who can say? – a kind of blessed insanity, like the bliss of a snake in the

winter sun...”. - Edward Abbey

"The world is big and I want to have a good look

at it before it gets dark". - John Muir

|

|---|

movie - Lone Pine Creek meets HST, Day 2, 11mb

(Click the image to view the movie)

|

|---|

|

Three map versions for your scrutiny: (the first version is fastest to load, the pdf version is good for printing, and the third map is

a web-based map that can be enlarged. You can change the base map (topo, etc.) and move across the HST. It will probably stop working

at some point and this is the reason I added the first two map formats.)

9-mile to Hamilton----> click for a JPG map.

9-mile to Hamilton----> click for a pdf map (large file,

decent for printing).

Another version of the map can be found here.

This web version can be enlarged and may be more useful than the above maps, assuming that

it works for you. ----> click here for the GPS visualizer map - and roam at will.

Day -2 photos - HST

Day 2: Martenique. Flooded out. To Hamilton Lake:

6 miles; up 2930', down 2300'; ERM = 16.4. Camp @ 8250'.

A rare harbinger of wild country, a Pine Marten pops across the trail as we labor

out of Buck Creek and towards Bear Paw, giving us a clear and exciting glimpse of this wily rascal. Wow. The Marten exudes

wilderness, and that's where he roams.

Scenic trump towers (dilapidated outhouses) appear along the HST at Bear Paw and

again at the now defunct High Sierra Camp.

We encounter Mr. Washington, of the NPS, cutting a yuge tree from the trail.

Soon there are wet foot Aspens and a glorious spring trickling off a mossy wall. At a

viewpoint farther along the trail, we see that the line of sister trees reaches far up the ridge.

Aspens as sister/brother trees: The leaves of aspen trees have long stems and a rounded shape that, together with

their size, makes them move in even a very light wind. Quaking.

The quaking aspen tree is a pioneer species that can quickly colonize areas recently cleared.

The trees develop root suckers which emerge from the soil around the base of the trunk. These suckers can grow into new trees,

forming a stand of closely growing aspens. As a result, the aspen poplar branching pattern creates tall, narrow trees with pyramid-shaped

crowns that can grow in proximity within a colony of aspens. Aspen is noted for its ability to regenerate vegetatively by shoots and

suckers arising along its long lateral roots. Root sprouting results in many genetically identical trees, in aggregate called a "clone." All

the trees in a clone have identical characteristics and share a root structure. The members of a clone can be distinguished from

those of a neighboring clone often by a variety of traits such as leaf shape and size, bark character, branching habit, resistance to

disease and air pollution, sex, time of flushing, and autumn leaf color. A clone may turn color earlier or later in the fall or exhibit a

different fall color variation from its neighboring aspen clones, thus providing a means to tell them apart. Aspen clones can be less

than an acre and up to 100 acres in size. There can be one clone in an aspen grove or there can be many.

The largest and oldest known aspen clone is the "Pando" clone on the Fishlake National

Forest in southern Utah. Also known as the “Trembling Giant”, it is a clonal colony of an individual male quaking aspen determined

to be a single living organism by identical genetic markers and believed to have one massive underground root system. It is over

100 acres in size and weighs more than 14 million pounds. That is more than 40 times the weight of the largest animal, a blue whale.

It has been aged at 80,000 years, although 5-10,000 year-old clones are more common.

A study published in October 2018 concludes that Pando has not been growing for the

past 30 to 40 years. Human interference was named as the primary cause, with the study specifically citing people allowing cattle

and deer populations to thrive, their grazing resulting in fewer saplings and dying trees.

Old aspen trees get sick, weak, and die, or a fire or other disturbance might kill them. Even

after they die, they provide homes and food for many small animals. The nutrients from decomposing wood and leaves return to the

soil where they are used by the new generation of flowering plants and trees. (parts from the USFS page "How Aspens Grow")

A purple-throated Sir Lizardó stops cavorting to watch us as we enjoy snack #1 from an Eagle

aerie viewpoint.

The next drop is into the abyss of Lone Pine Creek, where the HST is etched and trenched

into the granite pluton.

A pluton: (pronounced "PLOO-tonn") is a deep-seated intrusion of igneous rock, a body that made its way into pre-existing

rocks in a melted form several kilometers underground in the Earth's crust and then solidified. At that depth, the magma cooled and

crystallized very slowly, allowing the mineral grains to grow large and tightly interlocked — typical of plutonic rocks.

It's an overheating climb out of the Lone Pine gash.

I pause in the rare shade of a stately pine to eat an heirloom apple, courteous of Conner.

Delectable. Thanks Conner. The bonus is a spectacular view of sky castles. Gorgeous spires scraped and polished by glaciers of yoré.

The trail drops again before climbing into the Hamilton cirque, where we are greeted by a

gathering wind, portending a gathering storm. Quickly setting up tents, I poorly evaluate drainage. Barry does much better.

The storm cuts lose, with sheets of rain and hail so hard that I'm covered in tiny flakes of

duff and mud bounced under the tent fly. The storm rages on and water runs off the polished granite and slopes and before long the

tent and I are in a rising pond. Lightning hits so close that sound and flash are simultaneous and shocking. Electrifying.

I get out in the nude, holding my umbrella to attempt to dig a drainage outlet. No success.

So, I stuff everything I can into the pack, hide it under a sheltering pine and go in search of a

better tent site. The water is starting to flood into the tent when I return. Barry helps move the tent.

A bit later, the rain has tapered, then stopped, and we dry everything in sun and a strong breeze.

Fortunately, the sleeping bag was in a waterproof bag. Disaster averted.

"This I may say is the first time I

have been to church in California".

John Muir, after making the

first recorded ascent of Cathedral Peak in 1869.

|

|---|

movie - Big Arroyo Creek, Day 3, 5mb

(Click the image to view the movie)

|

|---|

|

Three map versions for your scrutiny: (the first version is fastest to load, the pdf version is good for printing, and the third map is

a web-based map that can be enlarged. You can change the base map (topo, etc.) and move across the HST. It will probably stop working

at some point and this is the reason I added the first two map formats.)

Hamilton to Big Arroyo----> click for a JPG map.

Hamilton to Big Arroyo----> click for a pdf map (large file,

decent for printing).

Another version of the map can be found here.

This web version can be enlarged and may be more useful than the above maps, assuming that

it works for you. ----> click here for the GPS visualizer map - and roam at will.

Day 3 photos - HST

Day 3: Pika Whispering. Through Kaweah Gap (10,700') to Old Big Arroyo Area:

6 miles; up 2900', down 1550'; ERM = 14.9. Camp @ 9700'.

The Pika harvests some grass and races to his hidden haystack beneath a granite boulder.

He comes back out to "eeek" at us and pose for his portrait. Barry's the one to hear and see them. Pika whispering. I say "them" because

we see three on the way to the Kaweah Gap, along with chubby Marmot, fawn deer, and cinnamon stick juniper - perhaps a cedar.

We start the climb to the gap early and inch up the well-designed trail. Passing the ancient

cinnamon red junipers (Incense Cedars?), we marvel at their apparent age, having bulky bases despite their short stature.

Arriving at the 180° turn in the trail, there's a long loop of steel cable coiled alongside the trail.

The trail passes through a keyhole tunnel and around to the other side of the deep abyss. "Ahh" I note "here's the reason for the cable.

" Cement abutments once anchored the cable, maybe for a swinging bridge? The bridge is long gone, replaced by the sharp angle trail.

Reaching Precipice Lake, we bask in some rare sunlight, then continue to the gap, where we see

a plaque dedicating Mt. Stewart (12,205') to the "father of Sequoia N.P."

George W. Stewart, editor and publisher of the Visalia Delta newspaper, was a very important man to Sequoia NP. He is

remembered as the “Father of Sequoia National Park” for his dedicated work to create and enlarge the Park by using the local newspaper.

He wrote many articles in advocating the preservation of the natural landscape and especially the big trees. His passing on September

7, 1931 was a tragic loss to all who knew him including those who had worked to establish the national forest. The following year on

August 30, 1932 the park installed a permanent bronze plaque on Mount George Stewart, in memory of his great efforts in our park.

This peak can be found on the Great Western Divide standing at 12,200 plus feet. (credit - Sequoia NP, NPS)

Rain sprinkles as Barry and I drop down the wide U of this glacier-scrubbed valley - El Big Arroyo.

Thunder cranks up as we reach tree line, and we pull off the trail at a decent, well-drained camp along cascades of the Big Arroyo Creek.

Some minor rain ensues, yet it's not much. However, the clouds and cool breeze continue, making thought of a decent bath unpleasant,

undesirable..

A long afternoon is savored watching diminutive fish in the swirls of Big Arroyo and drying the

last damp bits from yesterday's flood.

It's a delightful quiet camp with no bugs. This is different, in my experience from the situation near

the Old Big Arroyo patrol cabin and Bear boxes down the trail, where large squadrons of mosquitoes patrol the area.

|

|---|

movie - Cascade, Day 3, 9mb

(Click the image to view the movie)

|

|---|

|

"The power

of imagination makes us infinite". - John Muir

Three map versions for your scrutiny: (the first version is fastest to load, the pdf version is good for printing, and the third map is

a web-based map that can be enlarged. You can change the base map (topo, etc.) and move across the HST. It will probably stop working

at some point and this is the reason I added the first two map formats.)

Big Arroyo to Moraine Lake----> click for a JPG map.

Big Arroyo to Moraine Lake----> click for a pdf map (large file,

decent for printing).

Another version of the map can be found here.

This web version can be enlarged and may be more useful than the above maps, assuming that

it works for you. ----> click here for the GPS visualizer map - and roam at will.

Day 4 photos - HST

Day 4: Fantastic Foxtail. To Moraine Lake:

9.0 miles; ERM = 16.0; up 1600', down 1900'. Camp @ 9340'.

The well engineered trail climbs steadily from 9560' at the Big Arroyo Junction to somewhere

around 11,000' and into the magical mystical Foxtail Pine forest. Healthy and twisted, cinnamon-red ghost trees spaced generously through

a park of grizzly granulated granite. Gorgeous and enthralling trees. Spectacular.

It feels Grand to saunter across this high tableland. Then the trail begins to descend, erasing much

of the elevation gained.

The sign at the junction to Moraine Lake displays like the irrational exuberance of reckless wall

street and the wrong-headedness of trump, listing the mileage to the lake as 2.2 miles where the conservative estimate on the Tom Harrison

map is about 3 miles, a third longer. Of course, a bit of extra mileage does little damage while the trumpites and wall street hurt many decent

people. Can you say "asshole autocrat" or "plutocracy?"

Once again, it was a good idea to camp prior to the Big Arroyo Junction because we learn from some

youngster hikers that the Forest Service horses were walking noisily nearby, grazing, and that one was wearing a bell. We briefly hear the

sound of a chainsaw while climbing higher and higher above the Big Arroyo.

Taking the direct route to Moraine Lake, the vistas would be deluxe. Deluxe if not for the smoke

and haze clogging valleys, submerging the big peaks. Horrible.

Moraine Lake is a distinct bonus because we arrive in time to enjoy a tiny sandy beach, decent

smog filtered sun, and a strong breeze that aids laundry drying. I treat water rather than filtering it because the waves are churning particles.

Surprisingly, the top layer of water is warm, so I fill the bucket and locate a place for a bath in the lee of a nearby bump. Super.

Much of the day is friendly to solar panels, and the Lightsaver (4.9 ounces, by PowerFilm) is

loaded to 90% fully charged by the time we reach camp.

The erratics dot our campsite, and the strong breeze easily wraps around them. It's actually chilly

during the early evening.

The air cools, the wind subsides with the sun, and it's the close of Day 4 on the HST.

Erratics: Glaciers can pick up chunks of rocks and transport them over long distances. When they drop these rocks, they

are often far from their origin—the outcrop or bedrock from which they were plucked. These rocks are known as glacial erratics.

Erratics

record the story of a glacier's travels. Looking for the bedrock units that correspond with erratics can reveal complex flow patterns.

An excellent

example of how erratics can tell the story of past glaciations comes from Yosemite National Park: a field of erratics there contain rocks

that were plucked from an outcrop east of Tioga Pass, over the current watershed divide. These erratics reveal that the glaciers there

actually flowed uphill, over Tioga Pass. (from the NPS)

"Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken,

over-civilized people are beginning to find out going to the mountains is going home;

that wilderness is a necessity..". - John Muir

|

|---|

movie - Sky Parlor Meadow and the Kaweah Range, Day 5, 22mb

(Click the image to view the movie)

|

|---|

|

Three map versions for your scrutiny: (the first version is fastest to load, the pdf version is good for printing, and the third map is

a web-based map that can be enlarged. You can change the base map (topo, etc.) and move across the HST. It will probably stop working

at some point and this is the reason I added the first two map formats.)

Moraine Lake to riverside on the Kern----> click for a JPG map.

Moraine Lake to riverside on the Kern----> click for a pdf map (large file,

decent for printing).

Another version of the map can be found here.

This web version can be enlarged and may be more useful than the above maps, assuming that

it works for you. ----> click here for the GPS visualizer map - and roam at will.

Day 5 photos - HST

Day 5: Aromatic Descent. To streamside on the Kern River:

9.0 miles: ERM = 13.5; up 650', down 2800'. Camp @ 7100' estimated.

Reflections of Moraine Lake start the morning correctly, with delight.

Soon, the Sky Parlor Meadow appears, tawny grass a mellow foreground to views of the end of the Kaweah

Range and the skyline near Blackrock Pass across the Big Arroyo. Scenes clogged with smoke yesterday, now

seen in their full splendor. A solitary deer browses in Sky Parlor Meadow.

"“I don't like either the word [hike]

or the thing. People ought to saunter in the mountains - not 'hike!' Do you know the origin of that word saunter? It's a

beautiful word. Away back in the middle ages people used to go on pilgrimages to the Holy Land, and when people in

the villages through which they passed asked where they were going they would reply, 'A la sainte terre', 'To the Holy

Land.' And so they became known as sainte-terre-ers or saunterers. Now these mountains are our Holy Land, and we

ought to saunter through them reverently, not 'hike' through them.” . - John Muir

After some gentle roving, the trail drops and drops into the Kern drainage, passing

through refreshing wafting aromas of incense cedars and long needled pines beginning to bake in the gathering heat and

issuing a pleasant vanilla aroma.

From 6730' at the foot of the drop, and near the Kern River, we start upstream, traveling North.

Bells on NPS horses and mules are sylvan music among the ferns and thick underbrush.

Barry encounters part of the roaming herd while out filtering water. There are not many decent places to camp in the first two miles traveling up the Kern.

Chagoopa Falls flies over the rampant and is shrouded in smoke. There's not much of a

view today. Sigh.

Kern Hot Spring and scenic toilet are tempting, yet it's too hot and tomorrow too long to

dally. There is slippery mud on polished granite, and I slip and slide, collecting stinky thermal swamp yuck into everything on the

left side of the pack. Yuck is right.

Up the Kern we hike, alongside this roiling, rolling, young river, flowing clear and crisp to

the South. Finding a decent camp with high intensity stream background, Barry and I call it a day. I wash some items in an attempt

to remove the sour swamp stink while watching the river roll.

(Author's note: This area burned in the Rattlesnake Fire about a month after we hiked it. There were

yuge fires throughout the Sierra and California, destroying many precious areas. Sad.)

|

|---|

movie - Chagoopa Falls in the smoke, Day 5, 3mb

(Click the image to view the movie)

|

|---|

|

"The grand show is eternal. It is always

sunrise somewhere; the dew is never dried all at once; a shower is forever falling; vapor is ever rising. Eternal

sunrise, eternal dawn and gloaming, on sea and continents and islands, each in its turn, as the round earth

rolls". - John Muir

Three map versions for your scrutiny: (the first version is fastest to load, the pdf version is good for printing, and the third map is

a web-based map that can be enlarged. You can change the base map (topo, etc.) and move across the HST. It will probably stop working

at some point and this is the reason I added the first two map formats.)

riverside on the Kern to Wallace Creek at JMT/PCT junction----> click for a JPG map.

riverside on the Kern to Wallace Creek at JMT/PCT junction----> click for a pdf map (large file,

decent for printing).

Another version of the map can be found here.

This web version can be enlarged and may be more useful than the above maps, assuming that

it works for you. ----> click here for the GPS visualizer map - and roam at will.

Day 6 photos - HST

Day 6: Wrangling Wallace:

9.5 miles; up 3650, down 560; ERM = 17.9. Camp @ 10,400'.

Pan size trout swirl in the white gravel turbulence of Whitney Creek.

Cool air drifts down canyon, loaded with the aura of cedar. Alabaster cliffs glow in the early morning light.

It's Day 6 on the HST and Barry and I are gradually climbing along the Kern toward one

of the Junction Meadows (there are at least two Junction Meadows in the area) and a Bear box. There're numerous places to camp

along the way and good camping at the box and the junction where the trail to Colby Pass turns West.

Sadly, the smoke is filling the valley of the Kern, obscuring engaging vistas and ruining photo

opportunities.

What follows is the increased incline to where the HST turns East, away from the Kern and climbs

to 10,400' to meet the JMT, John Muir Trail, and the PCT, Pacific Crest Trail, at Wallace Creek.

Pausing at the junction near the Kern, we enjoy snack #2 in the welcome shade.

The pack stock grade trail feels continuous as it climbs toward the Wallace Creek junction.

We don't see anyone until we reach the Wallace Creek Junction. Clouds move in and it begins to sprinkle. Locating a camp not far

above Wallace Creek, we quickly set up camp and hide out during a brief storm. A coolish night ensues.

Three map versions for your scrutiny: (the first version is fastest to load, the pdf version is good for printing, and the third map is

a web-based map that can be enlarged. You can change the base map (topo, etc.) and move across the HST. It will probably stop working

at some point and this is the reason I added the first two map formats.)

Wallace Creek at JMT/PCT junction to Guitar Lake----> click for a JPG map.

Wallace Creek at JMT/PCT junction to Guitar Lake----> click for a pdf map (large file,

decent for printing).

Another version of the map can be found here.

This web version can be enlarged and may be more useful than the above maps, assuming that

it works for you. ----> click here for the GPS visualizer map - and roam at will.

Day 7 photos - HST

Day 7: Triumphant Tri-trail. Wallace Cr. to Guitar Lake:

7.6 miles. Up 2200, down 1120; ERM = 14.2. Camp @ 11,000'. On the HST, JMT, PCT to Crabtree. Then, it's duo-trail,

HST and JMT over Mt Whitney and out East to the Portal, not all of this today.

The trail rolls more than expected, gaining and then losing elevation, from

Wallace Creek and eventually we arrive at the JMT-PCT junction and turn East toward Crabtree and Whitney. Emerald

green moss and grass carpet the views across our morning meadows. Foxtail Pine dot the landscape, many bearing

the scars from lightning strikes.

It's a busy trail today and we encounter two groups that are hiking as one of 15

people. As I hike with JMT Griselda, the smiling Rain Woman, she reports that there are three large groups destined for Guitar Lake basin today.

Yikes. Grand Central Guitar, oh my.

At Crabtree Meadow, I go in search of the scenic toilet in the meadow and then visit

Ranger Chris at Crabtree RS (Ranger Station), where Chris points out another scenic toilet, this one for the RS. Photo.

A crackling, growling storm is moving in as Barry and I ascend toward Guitar Lake. Not

good. It's loud enough that I am prompted to put on the lucky rain pants in an attempt to avert a total immersion. It works, and

the trusty umbrella is enough to ward off the scattered rain. Orange light, filtered through the fire smoke, slants in after the

brief rain flurries.

While setting up camp on grizzly granite flakes near the Northern inflow to Guitar Lake, the

storm quits for the day. More hikers straggle in throughout the late afternoon.

More orange sunlight peeps through the clouds, this time adding some warmth. The clouds

retreat and part of the evening is quite lovely, accented by spectacular views of the Sierra Range. Jotting a few of these notes and

a footnote round out the early evening, in anticipation of an early tomorrow.

Three map versions for your scrutiny: (the first version is fastest to load, the pdf version is good for printing, and the third map is

a web-based map that can be enlarged. You can change the base map (topo, etc.) and move across the HST. It will probably stop working

at some point and this is the reason I added the first two map formats.)

Guitar Lake to Whitney to Outpost Camp----> click for a JPG map.

Guitar Lake to Whitney to Outpost Camp----> click for a pdf map (large file,

decent for printing).

Another version of the map can be found here.

This web version can be enlarged and may be more useful than the above maps, assuming that

it works for you. ----> click here for the GPS visualizer map - and roam at will.

Day 8 photos - HST

Day 8: A Very Good Beating. Whitney, to Outpost Camp:

10.7 miles; ERM = 36.3. Camp @ 10,400'.

Mount Whitney is the tallest mountain in the contiguous United States and the

Sierra Nevada, with an elevation of 14,505 feet.

The tracks of early hikers' headlamps mark the way up the switchbacks above Guitar

Lake. Orion lounges on his side just above the skyline. It's 4 a.m. and I'm up getting ready to hike when it's light. Others strive

to reach the Mt Whitney summit for sunrise.

So, I'm on the trail about 6 a.m. and plod steadily up and up to where the Whitney Trail

breaks from the JMT/HST. It's spattered rain at times, yet the developing views have been terrific. At the junction, I secure the

food bag, grab more clothing, and gasp toward the summit of Whitney (14,505'). Finally, I reach the highest point in the continental

US as a yuge flood of acrid smoke pours into the valley below.

There go the stunning views and photo opportunities. Sigh. I feel

happy that I snapped so many photos on the way up Whitney. A flood of emotion rolls over me, yet feels better than breathing smoke.

This is my third time on Mt. Whitney, yahoo.

After topping Trail Crest Pass at 13,600', next comes the tremendous downgrade, including

99 switchbacks above Trail Camp. Yikes.

Well into the hike down, I catch up with Barry, who skipped Whitney.

With creaking joints and sewing machine muscles, I'm feeling very happy to reach Outpost Camp.

Flakes of ash splash onto the once clean tent, a very dirty mudstorm. Ick. An orange fireball

sun drifts below the local horizon. The air quality is trumpian (bad, worst ever) and my eyes and lungs hurt.

During this adventure, we've traveled from Badwater Basin, the lowest point in North America

in Death Valley National Park at 282 ft below sea level to Mount Whitney, which is the tallest mountain in the contiguous United States

and the Sierra Nevada, with an elevation of 14,505 feet. Some would say "sea to summit," but not I because we didn't start our hike at Badwater.

Three map versions for your scrutiny: (the first version is fastest to load, the pdf version is good for printing, and the third map is

a web-based map that can be enlarged. You can change the base map (topo, etc.) and move across the HST. It will probably stop working

at some point and this is the reason I added the first two map formats.)

Outpost Camp to Whitney Portal----> click for a JPG map.

Outpost Camp to Whitney Portal----> click for a pdf map (large file,

decent for printing).

Another version of the map can be found here.

This web version can be enlarged and may be more useful than the above maps, assuming that

it works for you. ----> click here for the GPS visualizer map - and roam at will.

Day 9 photos - HST

Day 9: Double wag bag experience. To Whitney Portal and shuttle reverse. Eventually to Three Rivers:

4.0 miles; ERM = 10.0. Sleep @ 850'. Total HST distance = 71 miles; ERM = 161.4.

Clear skies start the day. The grunge of yesterday's mud/ash storm covers the tent. Ick.

Anything left out in the mud storm is, well, muddy with wet ash.

There's a gorgeous sheer wall above Outpost Camp, and it's deserving of a footnote. After a

second wag bag experience (the first was at Guitar Lake), something I would not characterize as a fun time, we get organized for the last

stretch of the HST. Thanks to Rick for the second wag bag.

Down we hike, enjoying the view of picturesque Lone Pine Lake, which is in the archaic path of the

glacier. Soon, we're out of the Whitney Zone and the hiker population palpably increases. It's growing warmer as we descend. Along the

way, we chat awhile with Anna and Adam, who are escaping from the smoke. Eric and Hanna blast past, on their way to Mammoth for some

hopefully smoke-free fun. We again see Jessica, Rick, and Alex as we approach the end of the HST at Whitney Portal.

Completioñ of the HST at 11:30 a.m. on August 25th. Yahoo!

We enjoy a hearty late breakfast at the Whitney Portal Store, under the supervision of Stellars Jays and

chipmunks. This is a traditional way to complete the HST, the JMT and it just feels right.

Now it's time to collect our bucket from the Bear box and start the less than fun trip around the Southern

horn of the Sierra to collect my Subie at the Alta Trailhead. Smoke clogs all the valleys we traverse on the reverse shuttle. My eyes burn from

the smoke and smog as we ply the numerous switchbacks, driving high to the Wolverton/Alta trailhead to retrieve the Subie Subaru. Both

Barry's and my Subie are coated with dried ash mud. Yuck. I'm reluctant to lower the window coated with this gunk, yet I enjoy the tour

back on the switchbacks with the window open, marveling at the sky-seeking Sequoias of the Giant Forest. Wow.

Barry and I end the day in Three Rivers, CA. Comfort it is.

Smoke rolls out when I unpack the sleeping bag. Ick. A yuge number of worthless email messages

flood the smartass when turned on, so I turn off this digital dithering. It's past hiker midnight (9 a.m.) when we get to bed.

Tomorrow is the long and hot drive back to the Colorado Plateau, and while driving I'll be reliving

the camaraderie of hiking and traveling with Barry and the joy of transnavigating the HST, High Sierra Trail. Stupendous.

"If a man walks in the woods for love of them

half of each day, he is in danger of being regarded as a loafer. But if he spends his days as a speculator, shearing off those woods and

making the earth bald before her time, he is deemed an industrious and enterprising citizen."

Henry David Thoreau, naturalist and author (1817-1862)

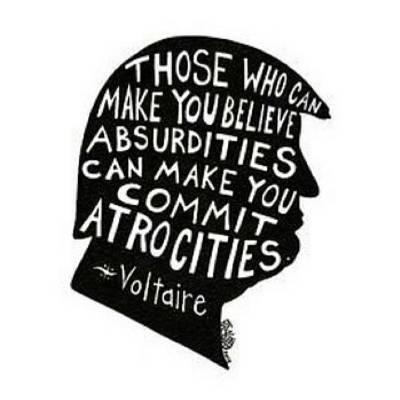

Noting the lie-filled discourse and psychopathology that substitutes for policy in the t-rump

administration, others have suggestions:

"Where is there dignity unless

there is honesty?". Cicero (106 BC - 43 BC)

"Anyone who has the power to make you believe absurdities has the power to make

you commit injustices". Voltaire, 1767

|

|---|

End of the HST, thanks Barry

(Click the image to see the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

trump towers of the HST

.

.

.

*ERM: Energy Required Miles, are there data to support this

mileage adjustment?

Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education and Leadership

Petzoldt first proposed his theory in his 1976 book “Teton Trails” to

help backpackers plan trips and calculate their energy needs on mountain trails. “Petzoldt defined one

energy mile as the energy required to walk one mile on the flat. He recommended adding two energy miles

for every 1,000 feet of elevation gain, so a person hiking one mile and 1,000 feet upward would use the

equivalent of three energy miles,” Phipps said.

Petzoldt’s energy mile theory was just a reflection of the mountaineer’s

“gut feeling,” Phipps said. The theory had never been tested in a laboratory before the study began in WCU’s

Exercise Physiology Laboratory in the spring of 2010, Phipps said.

To determine the validity of the theory, the study measured the energy cost

and perceived exertion for walking on flat ground, with and without a 44.5-pound backpack, and up an elevation

gain of 1,000 feet, with and without the backpack, through the collection of metabolic data, Phipps said.

Twenty-four student, faculty and staff volunteers, including 12 males and 12

females, went through four testing sessions as the research continued into fall semester of 2010. The study

results showed that the additional energy cost for ascending 1,000 feet ranged from 1.34 to 2.02 energy mile

equivalents, for an average of about 1.6 miles, compared to Petzoldt’s use of two energy miles for each 1,000

feet. The range revealed by the study was due to the “hikers” personal weight differences, Phipps said.

“It is remarkable that Petzoldt’s energy mile theory is so close to the actual energy cost measured during our

study,” Phipps said. “In the field of outdoor education, it’s important for leaders to include an estimation

of energy requirements during the planning of hiking trips.”

Phipps said the energy required for hiking up steep mountain trails would vary

for individuals and groups, and the variables of the trail would also factor in, but he recommends that

backpackers stick with Petzoldt’s idea of adding two energy miles for every 1,000 feet of elevation gain when

planning trips.

The Validity of Petzoldt's Energy Mile Theory, 2010

Authors: Maridy McNeff Troy, Maurice L. Phipps

Publication: Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership

.

.

.

All WV PCT, JMT, Sierra hike reports:

Click here or on the PCT trail marker to go to all WV reports about The PCT, JMT, Sierra hikes

|

|---|

Looking for All Wilderness Vagabond trip reports about the PCT, JMT, Sierra hikes?

Click the image to go to All WV reports about The PCT, JMT, Sierra hikes

|

|---|

|

.

.

.

Rob's note: In the below article, the MAGAvirus is referred to as the "caronavirus" or "COVID-19."

The Unraveling of America

Anthropologist Wade Davis on how COVID-19 signals the end of the American era

By

Wade Davis

https://www.RollingStone.com/politics/political-commentary/covid- 19-end-of-american-era-wade-davis-1038206/

Home Politics Political Commentary

Thurs. 6 August 2020

The COVID crisis has reduced to tatters the idea of American exceptionalism.

Wade Davis holds the Leadership Chair in Cultures and Ecosystems at Risk at the

University of British Columbia. His award-winning books include “Into the Silence” and “The Wayfinders.” His new book,

“Magdalena: River of Dreams,” is published by Knopf.

Never in our lives have we experienced such a global phenomenon. For the first time in the

history of the world, all of humanity, informed by the unprecedented reach of digital technology, has come together, focused on

the same existential threat, consumed by the same fears and uncertainties, eagerly anticipating the same, as yet unrealized, promises of medical science.

In a single season, civilization has been brought low by a microscopic parasite 10,000 times

smaller than a grain of salt. COVID-19 attacks our physical bodies, but also the cultural foundations of our lives, the toolbox of

community and connectivity that is for the human what claws and teeth represent to the tiger.

Our interventions to date have largely focused on mitigating the rate of spread, flattening

the curve of morbidity. There is no treatment at hand, and no certainty of a vaccine on the near horizon. The fastest vaccine ever

developed was for mumps. It took four years. COVID-19 killed 100,000 Americans in four months. There is some evidence that natural

infection may not imply immunity, leaving some to question how effective a vaccine will be, even assuming one can be found. And it

must be safe. If the global population is to be immunized, lethal complications in just one person in a thousand would imply the death of millions.

Pandemics and plagues have a way of shifting the course of history, and not always in a manner

immediately evident to the survivors. In the 14th Century, the Black Death killed close to half of Europe’s population. A scarcity of labor

led to increased wages. Rising expectations culminated in the Peasants Revolt of 1381, an inflection point that marked the beginning of

the end of the feudal order that had dominated medieval Europe for a thousand years.

The COVID pandemic will be remembered as such a moment in history, a seminal event whose

significance will unfold only in the wake of the crisis. It will mark this era much as the 1914 assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, the

stock market crash of 1929, and the 1933 ascent of Adolf Hitler became fundamental benchmarks of the last century, all harbingers

of greater and more consequential outcomes.

COVID’s historic significance lies not in what it implies for our daily lives. Change, after all, is the

one constant when it comes to culture. All peoples in all places at all times are always dancing with new possibilities for life. As companies

eliminate or downsize central offices, employees work from home, restaurants close, shopping malls shutter, streaming brings

entertainment and sporting events into the home, and airline travel becomes ever more problematic and miserable, people will adapt,

as we’ve always done. Fluidity of memory and a capacity to forget is perhaps the most haunting trait of our species. As history confirms,

it allows us to come to terms with any degree of social, moral, or environmental degradation.

To be sure, financial uncertainty will cast a long shadow. Hovering over the global economy for

some time will be the sober realization that all the money in the hands of all the nations on Earth will never be enough to offset the losses

sustained when an entire world ceases to function, with workers and businesses everywhere facing a choice between economic and

biological survival.

Unsettling as these transitions and circumstances will be, short of a complete economic collapse,

none stands out as a turning point in history. But what surely does is the absolutely devastating impact that the pandemic has had on the

reputation and international standing of the United States of America.

In a dark season of pestilence, COVID has reduced to tatters the illusion of American exceptionalism.

At the height of the crisis, with more than 2,000 dying each day, Americans found themselves members of a failed state, ruled by a

dysfunctional and incompetent government largely responsible for death rates that added a tragic coda to America’s claim to supremacy in the world.

For the first time, the international community felt compelled to send disaster relief to Washington.

For more than two centuries, reported the Irish Times, “the United States has stirred a very wide range of feelings in the rest of the world:

love and hatred, fear and hope, envy and contempt, awe and anger. But there is one emotion that has never been directed towards the U.S.

until now: pity.” As American doctors and nurses eagerly awaited emergency airlifts of basic supplies from China, the hinge of history opened

to the Asian century.

No empire long endures, even if few anticipate their demise. Every kingdom is born to die. The 15th

century belonged to the Portuguese, the 16th to Spain, 17th to the Dutch. France dominated the 18th and Britain the 19th. Bled white and

left bankrupt by the Great War, the British maintained a pretense of domination as late as 1935, when the empire reached its greatest

geographical extent. By then, of course, the torch had long passed into the hands of America.

In 1940, with Europe already ablaze, the US had a smaller army than either Portugal or Bulgaria.

Within four years, 18 million men and women would serve in uniform, with millions more working double shifts in mines and factories that

made America, as President Roosevelt promised, the arsenal of democracy.

When the Japanese within six weeks of Pearl Harbor took control of 90% of the world’s rubber supply,

the US dropped the speed limit to 35 mph to protect tires, and then, in three years, invented from scratch a synthetic-rubber industry that

allowed Allied armies to roll over the Nazis. At its peak, Henry Ford’s Willow Run Plant produced a B-24 Liberator every two hours, around

the clock. Shipyards in Long Beach and Sausalito spat out Liberty ships at a rate of two a day for four years; the record was a ship built in four

days, 15 hours and 29 minutes. A single American factory, Chrysler’s Detroit Arsenal, built more tanks than the whole of the Third Reich.

In the wake of the war, with Europe and Japan in ashes, the US with but 6% of the world’s population

accounted for half of the global economy, including the production of 93% of all automobiles. Such economic dominance birthed a vibrant

middle class, a trade union movement that allowed a single breadwinner with limited education to own a home and a car, support a family,

and send his kids to good schools. It was not by any means a perfect world but affluence allowed for a truce between capital and labor, a

reciprocity of opportunity in a time of rapid growth and declining income inequality, marked by high tax rates for the wealthy, who were by

no means the only beneficiaries of a golden age of American capitalism.

But freedom and affluence came with a price. The US, virtually a demilitarized nation on the eve of

the Second World War, never stood down in the wake of victory. To this day, American troops are deployed in 150 countries. Since the 1970s,

China has not once gone to war; the US hasn't spent a day at peace. President Jimmy Carter recently noted that in its 242-year history, America

has enjoyed only 16 years of peace, making it, as he wrote, “the most warlike nation in the history of the world.” Since 2001, the US has spent

over $6 trillion on military operations and war, money that might have been invested in the infrastructure of home. China, meanwhile, built

its nation, pouring more cement every three years than America did in the entire 20th century.

As America policed the world, the violence came home. On D-Day, June 6th, 1944, the Allied death

toll was 4,414; in 2019, domestic gun violence had killed that many American men and women by the end of April. By June of that year, guns

in the hands of ordinary Americans had caused more casualties than the Allies suffered in Normandy in the first month of a campaign that

consumed the military strength of five nations.

More than any other country, the US in the post-war era lionized the individual at the expense of

community and family. It was the sociological equivalent of splitting the atom. What was gained in terms of mobility and personal freedom

came at the expense of common purpose. In wide swaths of America, the family as an institution lost its grounding. By the 1960s, 40% of

marriages were ending in divorce. Only 6% of American homes had grandparents living beneath the same roof as grandchildren; elders

were abandoned to retirement homes.

With slogans like “24/7” celebrating complete dedication to the workplace, men and women

exhausted themselves in jobs that only reinforced their isolation from their families. The average American father spends less than 20

minutes a day in direct communication with his child. By the time a youth reaches 18, he or she will have spent fully two years watching

television or staring at a laptop screen, contributing to an obesity epidemic that the Joint Chiefs have called a national security crisis.

Only half of Americans report having meaningful, face-to-face social interactions on a daily basis.

The nation consumes two-thirds of the world’s production of antidepressant drugs. The collapse of the working-class family has been

responsible in part for an opioid crisis that has displaced car accidents as the leading cause of death for Americans under 50.

At the root of this transformation and decline lies an ever-widening chasm between Americans

who have and those who have little or nothing. Economic disparities exist in all nations, creating a tension that can be as disruptive as

the inequities are unjust. In any number of settings, however, the negative forces tearing apart a society are mitigated or even muted if

there are other elements that reinforce social solidarity — religious faith, the strength and comfort of family, the pride of tradition, fidelity

to the land, a spirit of place.

But when all the old certainties are shown to be lies, when the promise of a good life for a working

family is shattered as factories close and corporate leaders, growing wealthier by the day, ship jobs abroad, the social contract is irrevocably

broken. For two generations, America has celebrated globalization with iconic intensity, when, as any working man or woman can see, it’s

nothing more than capital on the prowl in search of ever cheaper sources of labor.

For many years, those on the conservative right in the US have invoked a nostalgia for the 1950s, and

an America that never was, but has to be presumed to have existed to rationalize their sense of loss and abandonment, their fear of change,

their bitter resentments and lingering contempt for the social movements of the 1960s, a time of new aspirations for women, gays, and people

of color. In truth, at least in economic terms, the country of the 1950s resembled Denmark as much as the America of today. Marginal tax rates

for the wealthy were 90 percent. The salaries of CEOs were, on average, just 20 times that of their mid-management employees.

Today, the base pay of those at the top is commonly 400 times that of their salaried staff, with many

earning orders of magnitude more in stock options and perks. The elite one percent of Americans control $30 trillion of assets, while the

bottom half have more debt than assets. The three richest Americans have more money than the poorest 160 million of their countrymen.

Fully a fifth of American households have zero or negative net worth, a figure that rises to 37% for black families. The median wealth of

black households is a tenth that of whites. The vast majority of Americans — white, black, and brown — are two paychecks removed from

bankruptcy. Though living in a nation that celebrates itself as the wealthiest in history, most Americans live on a high wire, with no safety

net to brace a fall.

With the COVID crisis, 40 million Americans lost their jobs, and 3.3 million businesses shut down,

including 41% of all black-owned enterprises. Black Americans, who significantly outnumber whites in federal prisons despite being but 13%

of the population, are suffering shockingly high rates of morbidity and mortality, dying at nearly three times the rate of white Americans.

The cardinal rule of American social policy — don’t let any ethnic group get below the blacks, or allow anyone to suffer more

indignities — rang true even in a pandemic, as if the virus was taking its cues from American history.

COVID-19 didn’t lay America low; it simply revealed what had long been forsaken. As the crisis

unfolded, with another American dying every minute of every day, a country that once turned out fighter planes by the hour could

not manage to produce the paper masks or cotton swabs essential for tracking the disease. The nation that defeated smallpox and

polio, and led the world for generations in medical innovation and discovery, was reduced to a laughing stock as a buffoon of a president

advocated the use of household disinfectants as a treatment for a disease that intellectually he could not begin to understand.

As a number of countries moved expeditiously to contain the virus, the US stumbled along in

denial, as if willfully blind. With less than four percent of the global population, the US soon accounted for more than a fifth of COVID

deaths. The percentage of American victims of the disease who died was six times the global average. Achieving the world’s highest

rate of morbidity and mortality provoked not shame, but only further lies, scapegoating, and boasts of miracle cures as dubious as the

claims of a carnival barker, a grifter on the make.

As the US responded to the crisis like a corrupt tin pot dictatorship, the actual tin pot dictators

of the world took the opportunity to seize the high ground, relishing a rare sense of moral superiority, especially in the wake of the

killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. The autocratic leader of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov, chastised America for “maliciously violating

ordinary citizens’ rights.” North Korean newspapers objected to “police brutality” in America. Quoted in the Iranian press, Ayatollah

Khamenei gloated, “America has begun the process of its own destruction.”

Trump’s performance and America’s crisis deflected attention from China’s own mishandling

of the initial outbreak in Wuhan, not to mention its move to crush democracy in Hong Kong. When an American official raised the issue

of human rights on Twitter, China’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson, invoking the killing of George Floyd, responded with one short phrase,

“I can’t breathe.”

These politically motivated remarks may be easy to dismiss. But Americans have not done

themselves any favors. Their political process made possible the ascendancy to the highest office in the land a national disgrace, a

demagogue as morally and ethically compromised as a person can be. As a British writer quipped, “there have always been stupid

people in the world, and plenty of nasty people too. But rarely has stupidity been so nasty, or nastiness so stupid”.

The American president lives to cultivate resentments, demonize his opponents, validate hatred.

His main tool of governance is the lie; as of July 9th, 2020, the documented tally of his distortions and false statements numbered 20,055.

If America’s first president, George Washington, famously could not tell a lie, the current one can’t recognize the truth. Inverting the

words and sentiments of Abraham Lincoln, this dark troll of a man celebrates malice for all, and charity for none.

Odious as he may be, Trump is less the cause of America’s decline than a product of its descent.

As they stare into the mirror and perceive only the myth of their exceptionalism, Americans remain almost bizarrely incapable of seeing

what has actually become of their country. The republic that defined the free flow of information as the life blood of democracy, today

ranks 45th among nations when it comes to press freedom. In a land that once welcomed the huddled masses of the world, more people

today favor building a wall along the southern border than supporting health care and protection for the undocumented mothers and

children arriving in desperation at its doors. In a complete abandonment of the collective good, US laws define freedom as an individual’s

inalienable right to own a personal arsenal of weaponry, a natural entitlement that trumps even the safety of children; in the past decade

alone 346 American students and teachers have been shot on school grounds.

The American cult of the individual denies not just community but the very idea of society. No one

owes anything to anyone. All must be prepared to fight for everything: education, shelter, food, medical care. What every prosperous and

successful democracy deems to be fundamental rights — universal health care, equal access to quality public education, a social safety net

for the weak, elderly, and infirmed — America dismisses as socialist indulgences, as if so many signs of weakness.

How can the rest of the world expect America to lead on global threats — climate change, the

extinction crisis, pandemics — when the country no longer has a sense of benign purpose, or collective well-being, even within its own

national community? Flag-wrapped patriotism is no substitute for compassion; anger and hostility no match for love. Those who flock

to beaches, bars, and political rallies, putting their fellow citizens at risk, are not exercising freedom; they are displaying, as one

commentator has noted, the weakness of a people who lack both the stoicism to endure the pandemic and the fortitude to defeat it.

Leading their charge is Donald Trump, a bone spur warrior, a liar and a fraud, a grotesque caricature of a strong man, with the backbone of a bully.

Over the last months, a quip has circulated on the internet suggesting that to live in Canada today

is like owning an apartment above a meth lab. Canada is no perfect place, but it has handled the COVID crisis well, notably in British Columbia,

where I live. Vancouver is just three hours by road north of Seattle, where the US outbreak began. Half of Vancouver’s population is Asian,

and typically dozens of flights arrive each day from China and East Asia. Logically, it should have been hit very hard, but the health care system

performed exceedingly well. Throughout the crisis, testing rates across Canada have been consistently five times that of the US. On a

per capita basis, Canada has suffered half the morbidity and mortality. For every person who has died in British Columbia, 44 have perished

in Massachusetts, a state with a comparable population that has reported more COVID cases than all of Canada. As of July 30th, even as rates

of COVID infection and death soared across much of the US, with 59,629 new cases reported on that day alone, hospitals in British Columbia

registered a total of just five COVID patients.

When American friends ask for an explanation, I encourage them to reflect on the last time they

bought groceries at their neighborhood Safeway. In the US there's almost always a racial, economic, cultural, and educational chasm

between the consumer and the check-out staff that is difficult if not impossible to bridge. In Canada, the experience is quite different.

One interacts if not as peers, certainly as members of a wider community. The reason for this is very simple. The checkout person may

not share your level of affluence, but they know that you know that they are getting a living wage because of the unions. And they

know that you know that their kids and yours most probably go to the same neighborhood public school. Third, and most essential,

they know that you know that if their children get sick, they will get exactly the same level of medical care not only of your children

but of those of the prime minister. These three strands woven together become the fabric of Canadian social democracy.

Asked what he thought of Western civilization, Mahatma Gandhi famously replied, “I think

that would be a good idea.” Such a remark may seem cruel, but it accurately reflects the view of America today as seen from the

perspective of any modern social democracy. Canada performed well during the COVID crisis because of our social contract, the bonds

of community, the trust for each other and our institutions, our health care system in particular, with hospitals that cater to the medical

needs of the collective, not the individual, and certainly not the private investor who views every hospital bed as if a rental property. The

measure of wealth in a civilized nation is not the currency accumulated by the lucky few, but rather the strength and resonance of social

relations and the bonds of reciprocity that connect all people in common purpose.

This has nothing to do with political ideology, and everything to do with the quality of life. Finns

live longer and are less likely to die in childhood or in giving birth than Americans. Danes earn roughly the same after-tax income as

Americans, while working 20% less. They pay in taxes an extra 19¢ for every dollar earned. But in return they get free health care, free

education from pre-school through university, and the opportunity to prosper in a thriving free-market economy with dramatically

lower levels of poverty, homelessness, crime, and inequality. The average worker is paid better, treated more respectfully, and rewarded

with life insurance, pension plans, maternity leave, and six weeks of paid vacation a year. All of these benefits only inspire Danes to work

harder, with fully 80% of men and women aged 16 to 64 engaged in the labor force, a figure far higher than that of the US.

American politicians dismiss the Scandinavian model as creeping socialism, communism lite,

something that would never work in the US. In truth, social democracies are successful precisely because they foment dynamic capitalist

economies that just happen to benefit every tier of society. That social democracy will never take hold in the US may well be true, but,

if so, it is a stunning indictment, and just what Oscar Wilde had in mind when he quipped that the US was the only country to go from

barbarism to decadence without passing through civilization.

Evidence of such terminal decadence is the choice that so many Americans made in 2016 to

prioritize their personal indignations, placing their own resentments above any concerns for the fate of the country and the world, as

they rushed to elect a man whose only credential for the job was his willingness to give voice to their hatreds, validate their anger, and

target their enemies, real or imagined. One shudders to think of what it will mean to the world if Americans in November, knowing all

that they do, elect to keep such a man in political power. But even should Trump be resoundingly defeated, it’s not at all clear that such

a profoundly polarized nation will be able to find a way forward. For better or for worse, America has had its time.

The end of the American era and the passing of the torch to Asia is no occasion for celebration,

no time to gloat. In a moment of international peril, when humanity might well have entered a dark age beyond all conceivable horrors,

the industrial might of the US, together with the blood of ordinary Russian soldiers, literally saved the world. American ideals, as

celebrated by Madison and Monroe, Lincoln, Roosevelt, and Kennedy, at one time inspired and gave hope to millions.

If and when the Chinese are ascendant, with their concentration camps for the Uighurs,

the ruthless reach of their military, their 200 million surveillance cameras watching every move and gesture of their people, we will

surely long for the best years of the American century. For the moment, we have only the kleptocracy of Donald Trump. Between

praising the Chinese for their treatment of the Uighurs, describing their internment and torture as “exactly the right thing to do,”

and his dispensing of medical advice concerning the therapeutic use of chemical disinfectants, Trump blithely remarked, “One day,

it’s like a miracle, it will disappear.” He had in mind, of course, the coronavirus, but, as others have said, he might just as well have

been referring to the American dream.

.

.

.

Links and books:

Bill McKibben – suggested books include: Falter, Maybe One, Eaarth, The End of Nature

Click here to: see the First ascent of El Capitan, Argosy Magazine, 1959 (10 pages) 22 MB.

Link to all WV reports about hiking The Grand Canyon

Link to all WV reports about hiking the JMT, PCT, Sierra hikes

Link to Scenic Toilets of Inner Earth: Scenic Scatology of the Wilderness Vagabond

Marc Reisner (1993) Cadillac Desert: The American West and Its Disappearing Water,

Revised Edition, Penguin Books

McPhee, John (1982) Basin and Range Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Mount Whitney High Country map (2018), Tom Harrison Maps

.

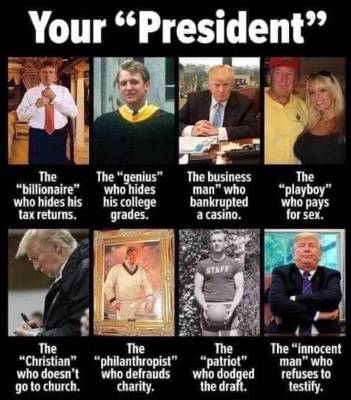

More Truth Than Joke:

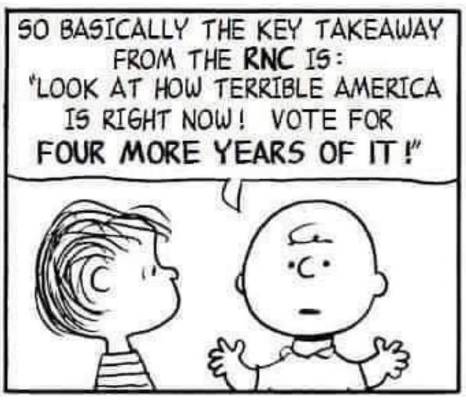

|

|---|

4 more years of destruction

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

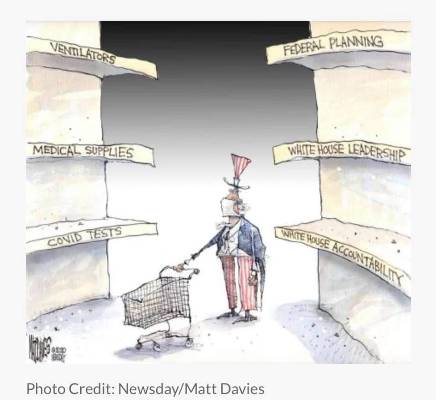

|---|

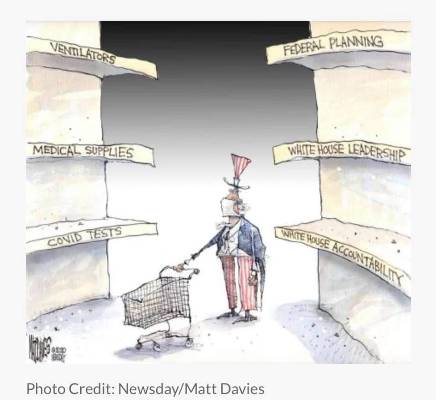

bare shelves

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

Barr - choke hold on justice

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

gop criminals

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

.

"What luck for the rulers that

men do not think". - Adolph Hitler

.

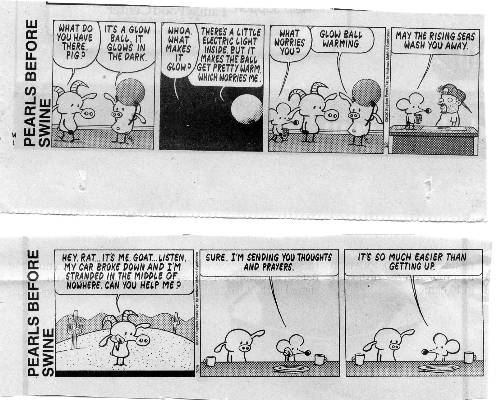

|

|---|

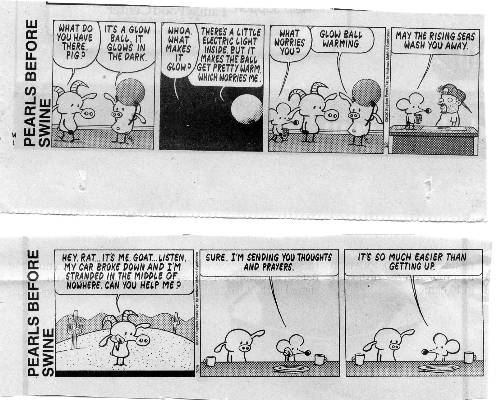

glow ball

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

STD

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

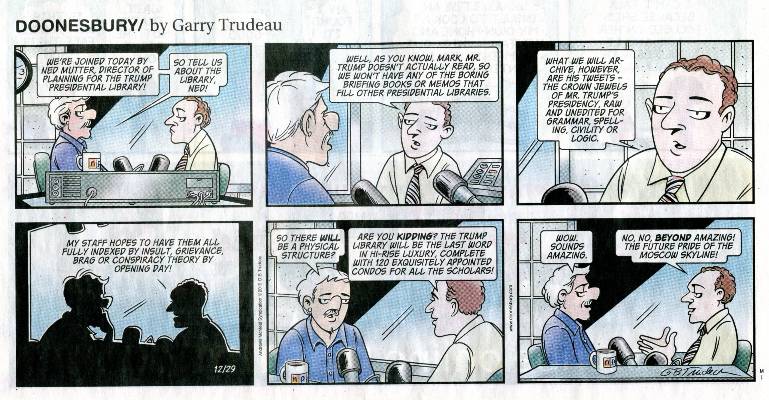

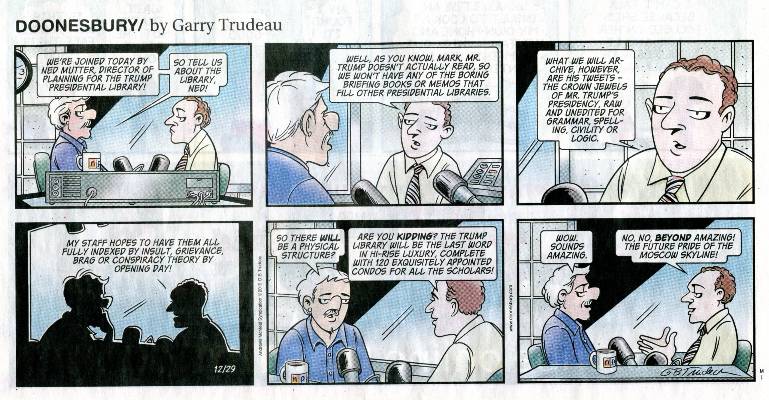

trump library, Russia

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

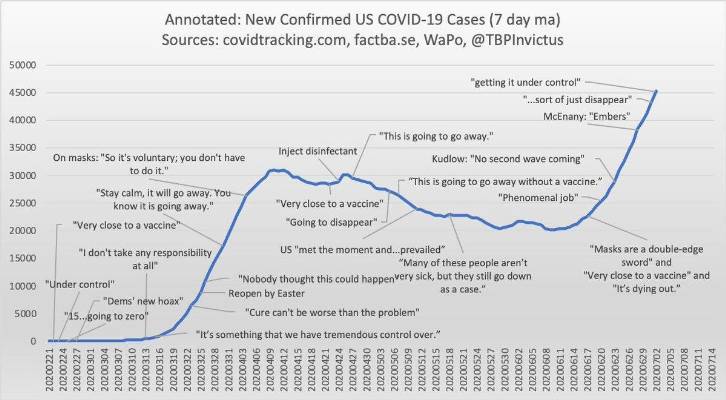

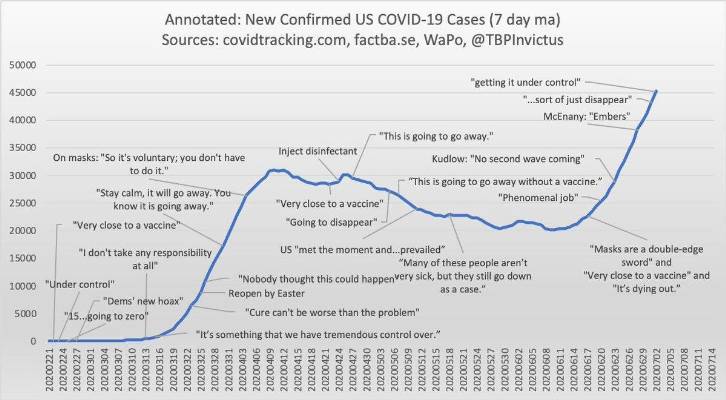

MAGAvirus under control?

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

unnecessary deaths

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

Voltaire

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

fake president

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

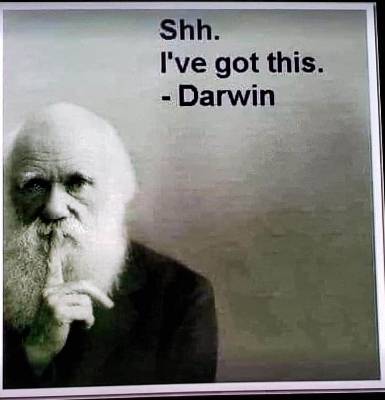

|---|

No mask? Darwin Award in progress

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

all the difference

(Click the image for the full-size image)

|

|---|

|